When the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly

employment report for January, it also released revisions to data

for all of 2012, revisions that were remarkably more positive than

what had been previously reported. In total, 647,000 more jobs were

created in the United States last year than BLS reports had

indicated. While that is only about 0.41 percent of total U.S.

workforce, it significantly alters the estimate of year-over-year

growth. As of January, before the adjustment, total employment

year-over-year was up less than 1.2 percent. With the adjustment,

average growth in 2012 grew to more than 1.5 percent, in line with

the 40 year average, and well above the 20 year average of 1.1

percent annual growth. In fact, in the last 10 years employment has

only grown an average of 0.3 percent per year. By these metrics,

2012 was at least an average year for employment growth and in

recent history was actually above average.

This year, however, is already presenting new challenges and

changing dynamics. The debt crisis in Europe has backed off from

the cliff, putting a pin back in one of the largest potential

economic grenades on the horizon. Yet, the cost-cutting effects

from sequestration appear increasingly unavoidable and will in the

coming months have measurable consequences across the military,

military support, research, education and other sectors that rely

heavily on government support.

While the cuts will have a rapid near-term effect on employment,

they may also create a temporary talent acquisition opportunity for

employers. Many of the positions affected are filled by highly

trained people in disciplines that have continued to experience

increasing talent shortages in recent years.

“In layoffs like these, that have nothing to do with job

performance but rather fallout from much larger issues, highly

qualified and capable people end up entering the job market,” says

Rob Romaine, president of MRINetwork. “It

means a short window of availability for private sector employers

to scoop up experienced professionals in disciplines like

engineering, IT, accounting, and project management.”

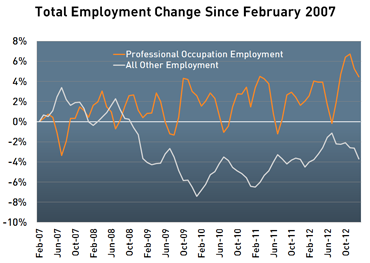

Total employment in the U.S. shrank by more than 6 percent

during 2008 and 2009. Yet, despite comprising more than 20 percent

of the U.S. workforce, employment of those in professional and

related occupations remained essentially flat during those years

and has since resumed its pace of growth.

“Historically, government layoffs in sectors like defense have

had only a short-term impact on employment because the types of

people who are laid off are inherently highly employable,” notes

Romaine. “While these cuts will be reaching far beyond defense

spending, the principle still applies for many of the industries

that will be affected, which points to an opportunity for

employers.”

This isn’t to say that sequestration will be a big boon for the

U.S. economy. Many economists project sequestration will remove as

much as 1.5 percent of GDP from the economy in 2013 and blame it

for the sharp decline in GDP growth during the 4th quarter of

2012. Private-sector activity, however, is rebounding, and in the

4th quarter was enough to counter nearly a 15-percent drop in

government expenditure and keep total GDP growth virtually

flat.

“There was such a shortage of experienced talent before the

recession that even with the sharpest economic decline in more than

a generation, professional employment levels didn’t decline,” notes

Romaine. “While the economy may slow again by the end of the year,

we shouldn’t expect that to lower the demand for professional

talent nor affect the availability of experienced

professionals.”

Login

Login